Welcome back to the Wayward Children reread! Today, in our final installment, we head to the Goblin Market seeking fair value for our travails. Spoilers ahead for In An Absent Dream. It’s available now, and I encourage you to pick up a copy (on sale for six sharp pencils and a quince pie, if you can find the right market stall) and read along!

Jack Wolcott would tell you that lightning carries power—but thunder is how that power travels beyond the reach of vision. It wakes you in the middle of the night, turns your head, draws you to the window to find out what happened. Count the seconds of suspense between light and sound, and discover how close you stand to that flash of danger and possibility.

I’ll read about lightning all day, but there’s a special place in my heart reserved for stories of thunder. What happens after the climactic confrontation, the eucatastrophic change, the dramatic loss? I want the nitty-gritty politics of Leia rebuilding a just society after the revolution. I want Superman to finish defeating the monster and start cleaning up the rubble left by the fight. I want heroes, finally given a moment to rest, forced to cope with what happened to them.

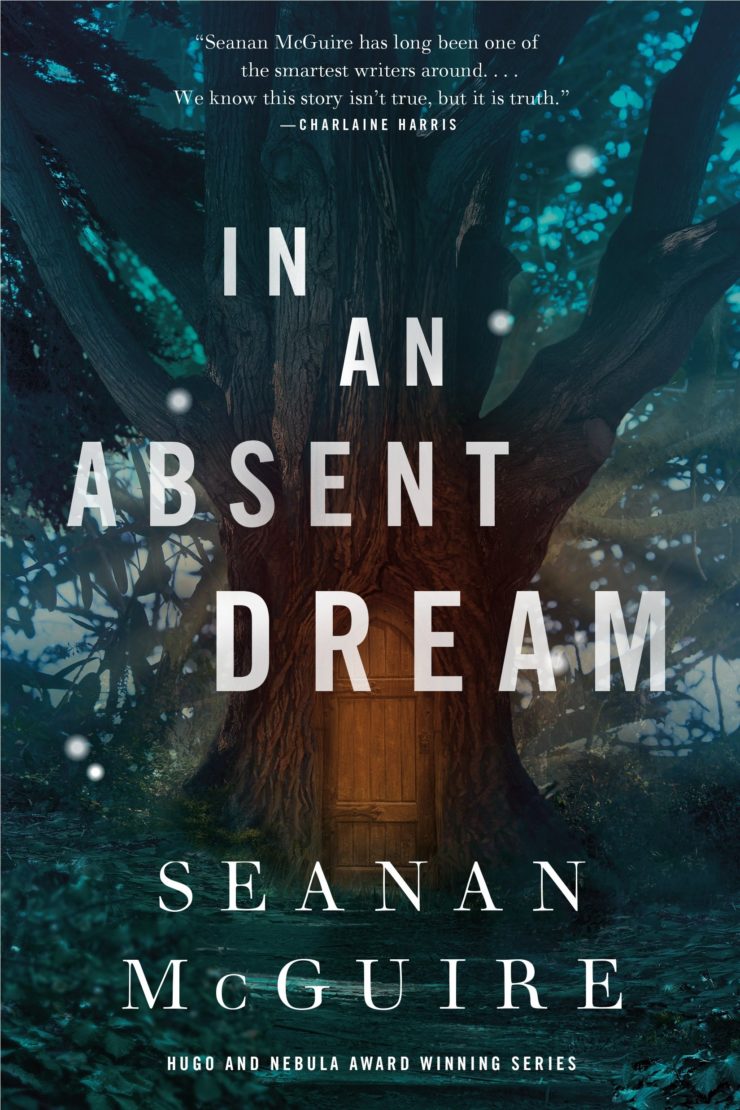

Buy the Book

In An Absent Dream

The Wayward Children series is all about the thunder. Even looking back at the students’ time before they came to the school, these books are still more interested in the consequences of adventure than adventure itself. And so it is with the latest entry, In an Absent Dream, covering Lundy’s years at the Goblin Market.

We first met Lundy in Every Heart a Doorway, where she was acting as counselor and second-in-command at Eleanor’s school. And where she died, her brain stolen by Jill in an effort to make a “perfect girl” as a skeleton key to the Moors. Lundy looked like a young girl and acted like an older woman; Eleanor explained that she was aging backwards, the result of a deal to try and avoid getting too old for the Goblin Market.

So we start Lundy’s story already knowing the end: she makes that deal, and loses her place in the Market anyway. You’d expect the flashback to be all about causes, a story of lightning. But even here, McGuire focuses on aftereffects. In the market Lundy’s a hero, a warrior against the Wasp Queen and the Bone Wraiths. She fights for great stakes, loses her beloved friend Mockery in battle. But we learn of these epic adventures only afterwards, while following their impact on Lundy and her best friend Moon. What matters isn’t which weapons were raised or how the narrow escapes occurred, but how they change the girls’ relationships to each other and to the Market itself. What matters is how the echoes of Lundy’s quests lead her to her final, unavoidable mistake.

The bright, bold events that shake worlds are hidden in cracks, and the tale on the pages is a subtler one. Jack and Jill fled from abuse and from family expectations so tight that their true selves were entirely stifled. Katherine Lundy’s problems aren’t quite so dramatic. Her family’s loving, flexible enough to let a serious young girl be more interested in books than dresses. But her father’s the school principal, and while she decides early on to be okay with the distance that puts between her and her peers, it doesn’t exactly give her a lot of strong ties to Earth. And as she grows older, and the 60s fade into the 70s, the place she’s allowed to fill grows narrower. No one wants a girl—even a girl who’s good at following the rules—to love books more than people forever.

Also unlike Jack and Jill, well-read Katherine has some clue what’s going on when she walks through a door, in a tree that isn’t normally there, and finds herself in a hallway emblazoned with rules. She takes them in, and takes comfort in their existence: Ask for nothing; names have power; always give fair value, take what is offered and be grateful… and most confusing of all, “remember the curfew.” From the corridor she comes out into the terrifying, delightful, wonder-filled Market. Within a few minutes she’ll meet Moon, a market-born native about her own age, and the Archivist, who explains the rules and offers access to her books, in exchange for the fair value of treating them well and telling the older woman what she thinks of them.

The “curfew” is key to the Market’s Doors. This isn’t a place you tumble into once and then lose forever. Instead, its Doors open for visitors again and again, in both directions—until you turn 18. Before that birthday, you must either take the oath of citizenship and remain in the Market, or leave it behind forever.

Over the years, Lundy travels between Earth and the Market several times. Usually she intends to stay on either side for only a few minutes—to get away from irritating teachers on Earth, to mourn a friend lost on a quest, or just to pick up trade goods. But inevitably, she’s drawn in by each world’s temptations. The Market has freedom and friends, a growing apprenticeship to the Archivist, a unicorn centaur who sells the sweetest pies. Earth has the love and duty she bears her family.

Earth has Lundy’s father, who visited the Goblin Market himself when he was young—who chose Earth, and wants her to do the same.

Ultimately, she can’t choose. I suspect it’s Eleanor’s own experiences and expectations that lead her to describe Lundy’s final, desperate deal the way she did—as a last-ditch attempt to keep access to the Market. But in fact, it’s a last-ditch attempt to have both, to give herself just a little more time before she’s forced to abandon one world forever. Instead that attempt to twist the rules gets her kicked out forever, suffering the consequences of the deal for which she begged.

Directions: The Goblin Market is a realm of strict rules and absolute, magically-enforced fairness. It’s logical, and may be virtuous too—depending on how you feel about the Market’s definitions of fair value, and about its absolute intolerance for loopholes.

Instructions: The core rule of the Market is “fair value” – everything else, even the curfew, follows in some way from that central standard of exchange. What’s fair depends on how much you have, how much you’re able to do, and the intent behind your actions. And it’s the world itself that enforces that fairness. Incur debt and feathers grow from your scalp, talons from your nails. Incur enough, and you’ll become a bird flitting through the forest or caged at its edge, carrying messages to try and regain your humanity—or losing yourself entirely in flight and feathers.

Tribulations: Danger comes from the vulnerabilities bared by asking directly for what you want, or by sharing your true name. Give your name, and you’ve given yourself away. Ask for something, and you’ve promised to accept whatever price is set.

Lundy’s door bears the same warning as the door to the Moors: “Be Sure.” The Lord of the Dead makes a similar demand of Nancy, so we’ve now encountered this injunction in three separate, very different worlds. They’re all Logical, though. Is that coincidence, or the heart of that particular Compass direction? I suspect the latter. It’s hard to imagine, say, Confection, demanding certainty from its immigrants. But since these are the only four to worlds we’ve seen close up at all, it’s hard to tell whether that’s actually the important distinction.

Jack and Jill learn their sureness on the Moors, but for young Lundy being sure is practically a superpower. It’s the loss of sureness that’s ultimately her undoing—and in some ways that loss grows out of its opposite. So self-contained at the tender age of six, she’s never forced to deal with truly incompatible desires until she’s old enough, her heart big enough, to love two worlds. That sort of complexity is a natural part of growing up. It’s Lundy’s ill luck to hit that particular milestone at just the wrong time—before she’s learned to understand, at a gut level, that sometimes you have to make the heart-rending choice anyway. I have to confess that at 43, I can’t say how she should have chosen. Either way she was going to break someone’s heart, not counting her own. And of course failing to choose—committing the deadly sin of being unsure in a world where certainty is the first rule—leaves both worlds heartbroken.

Lundy’s father clearly knows something of the Market’s cruelty. He knows magic exists, and has deliberately turned his back on it. What he tells Lundy, when they finally talk openly, is that a world that enforces fairness magically is a world with no true fairness at all, no chance to choose generosity on your own. But he also shudders at the thought of the Market’s debts, and “would have sooner died” than let himself become a bird even for a moment. We know from the Archivist that while permanently choosing “feathers over fairness” is rare, many people go feather-clad for at least a little while—Lundy’s father’s revulsion isn’t exactly universal.

And yet he’s right that it’s different to choose Earth, with all its complexities and atrocities, and that it makes him a better father to have done so. Even the principle of fair value, that he’s rejected so forcefully, ultimately leads him to negotiate with his daughter as a real person with legitimate desires of her own. That kind of respect is pretty rare for any father whose daughter is nearing adulthood, and wasn’t exactly more common in the 60s.

Out of all the parental relationships in the series so far, this seems like the healthiest save for Sumi’s family on Confection. Lundy and her father actually talk with each other, openly and honestly. He knows what she’s been through, covers for her absences—and tries desperately to ensure that she makes the same choice he did. That’s a problem, and probably a major reason why her indecision happens as it does. And yet, it’s pretty damn understandable. It’s not just that he wants her to share his values. It’s that he wants to have his kid where he can see her sometimes. I can’t blame him for that, any more than I can blame Lundy for not wanting to abandon either Moon or her sister. It’s only the Market where these things are unforgivable.

So is the market actually fair? Sitting in the middle of late-stage capitalism, there’s something very appealing about a place that enforces swift and public justice against those who try to take advantage. The Archivist describes things that will earn you feathers: charging someone too much for the food and shelter required to survive, for example. Or demanding a single ribbon from both someone who has a hundred ribbons and someone who only has one to begin with.

Everything in the market has a cost—but it’s gone so far into capitalism that it’s come out the other side into “to each according to their needs, from each according to their ability.” This flavor of fairness may lead to outcomes that make the reader shudder—but of course the unfairnesses of Earth can be far nastier, and do far worse than turn a few people into birds or force one indecisive girl to age backwards. Throw the people responsible for student loans and housing bubbles into the Goblin Market for a few days, and you’re going to have a nasty flock of vultures flying around.

Behind every Door is the answer to a bone-deep need. The Moors give people the chance to become themselves, unfettered by the constraints of virtue or natural law. The Underworld offers stillness, strength, and uninterrupted time for contemplation. Confection is a cozy hearth where there’s always food enough to nourish body and soul.

And the Market? The Market is a respite from Earth’s unfairness, from the need to brace yourself against the possibility of cheaters and con artists, or just people with the power to charge more than you can afford. It’s a place where trust is unnecessary yet easy, where necessities will always be affordable, and where no citizen will ever need to question whether she’s doing enough for her community. All things considered, it’s a surprise that more Doors don’t open there.

And yet, at the end of our tour of the Compass, I don’t think any of these worlds could tempt me to stay forever. My favorite spot is still Kade’s attic at the school. More than any one kind of magic, I’m still attracted to that spot at the center where students arrive with an endless array of stories, a thousand different needs—and a home that never needs to settle into a single truth.

Note: Comments are now open to spoilers for all four books.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.